“In the fading evening light, echoes of a timeless span began to die away, and through the windows the sky in the misty distance was tinted with the rosy half-tones of twilight.”

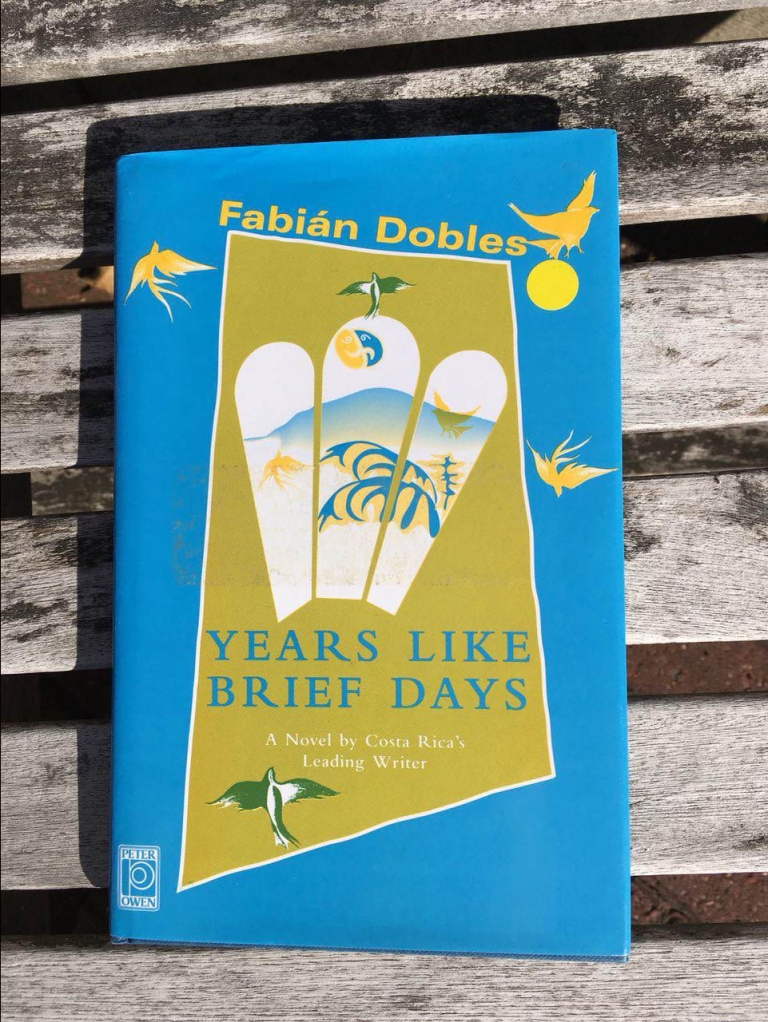

Years Like Brief Days

by Fabián Dobles

I have drawn my choice for Costa Rica from the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works , an assortment of translated ‘masterpieces of world literature’. For this reason, I had high hopes for this novel by one of the most eminent Costa Rican authors, Fabián Dobles.

Set some time in the past (the 1980s?), this novel depicts a seventy-year-old man retracing the steps of his youth after being drawn to revisit the town he grew up in, “in response to something fascinating and mysterious”.

Jaded by modern life, (“living cross-eyed by computers“) he drives there in his old van, “urged to follow” the desire to recapture something of his younger years “attracted by the mahogany trees, the cicadas and the hills” and calls his wife from the road to say that he’s now undertaking the trip that they’d planned to do together alone.

This nostalgic journey evokes a whole host of lost boyhood memories and through a series of reminisces and vivid dreams while napping in the van, he begins to remember his childhood years and adolescence. From his family home full of chatter, life and music and his severe father, the village doctor, to his first experiences with religion: “he held tight and swallowed, and without really listening heard about God and the Ten Commandments, the Devil and his eternal fire, care for those badly brought up, and sin, sin, sin” to his first sexual encounters.

After his initial visit, he returns home and the second part of the novel begins as he pens a letter to his mother (long since deceased) he never had the chance to write to her during her lifetime, which reflects on times passing, and his anger and resentment at being sent away to a seminary school in San José.

The man, who as a boy was more concerned with worldly pleasures (“you’ll never make this lad don a surplice…he was born to love”) found little comfort in religion, considering it hypocritical and incompatible with the world around him: “the world was divided into two parts: one very large, immense, full of prohibited and sinful possibilities, and the other, too small and limited, full of permitted possibilities: EVIL and good; the big SINS and the little virtues“. The man considers the effort of his family “to make him an altar boy” a cynical ploy to better their own positions “so that he can help all relatives to become important here on earth and above in the beyond” and finds that his growing secularity becomes at odds with his mother’s devoutness “my calendar of Saints Days was beginning to get filled up with other names: the blessed Galileo Galilei, the blessed Isaac Newton, St Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the archangels Voltaire and Montesquieu“.

His ill-feeling towards his family for the “all that insane hell you dragged me into” is heightened when in the seminary he receives his attentions of a predatory priest. The boy is only spared from sexual abuse (or “Dionysiac impalement” as he terms it) by being sick after the priest has plied him with alcohol.

Sometime later, as he speaks with his ailing father on his deathbed, as his father warns him not to get taken in by either religion or priests who, he says, are “not angels. They’re human” – the boy can only think “and you’re the one to warn me now, you old son-of-a-bitch?”.

Sad and yet tinged with humour, the narrative continues and the latter third of the novel delves into the narrators’ relationship with this older brother and tales of the two of them horse-riding and horse dealing, are juxtaposed with fraternal quarrels and an eventual falling out, for which he regrets not making amends. These events, “so long ago and so many lives ago that I can barely remember it” coincide with recollections of a typhoid epidemic coursing through his family, and village, which his doctor father heroically treats by making “use of all powers – his worldy ones, and those others, from above the clouds and in the storms“.

In the coda to the novel, the man returns to the town of his childhood (this time with his wife), he continues to reminisce and through sobs, relates to his wife how he has forgiven his family, particularly his father, who a man of principle (“I didn’t study medicine to make money” ), for all his strictness, taught him valuable lessons on personal integrity: “his bad-tempered constraints, prepared me for life“.

Dobles writes well, and I particularly enjoyed the depictions of nature: “the anis that were there before were circling around now and settling on the cattle in search of ticks. The jays were in abundance and the golden oriole nests swaying in the wind in a pejibayero palm tree” and the lush descriptions of the narrator’s world, which were almost Steinbeckian “..how deafening the cicadas were, how the trees flourished, the blackbirds sang of rain; that iguana was motionless, this squirrel was timid”, however, this is not a novel I would recommend.

At times farcical and painful and at times peppered with earthy humour and unexpected references to bodily functions, this novel was a strange one. Ostensibly a reflection on time passing and questions on faith and family, this was a very nuanced novel, that was perhaps too subtle for my understanding. Upon finishing the book, I had a strange sense of dissatisfaction, as if I’d missed some crucial aspect that had prevented my complete understanding. It was like I had taken in the words but could not extrapolate any deeper meaning.

If anyone has had different experiences with this novel, please let me know. Would love to hear another perspective!

p.s. despite my enjoyment of the natural elements, at times I felt like the novel could also have benefitted from a glossary. I am not that familiar with Costa Rican flora, so sentences like this were a bit of a mystery: “this is a cedar, that’s a laurel. There’s a pochote, a guapino, a guarumo, a largatillo, a nance, a jinocuabe“.

p.s. forgot to mention the excellent translation by Joan Henry!